news

This category contains the following articles

- Return of the art fairs: Frieze London and Frieze Masters to open in Regent's Park

- Maxwell Alexandre, Conny Maier, Zhang Xu Zhan: Deutsche Bank's "Artists of the Year" at the PalaisPopulaire

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Rana Begum, WP 410-412, 2020

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Franziska Furter, Draft IX/V, 2010

- Kunstsammlung NRW - Everyone is an artist. Cosmopolitan exercises with Joseph Beuys

- Royal Academy of Arts - David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Fabian Marti, Untitled, 2011

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Jo�o Maria Gusm�o + Pedro Paiva

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Beat Zoderer, Polygon I-VI, 2019

- Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt - Gilbert & George: The Great Exhibition

- Ways of Seeing Abstraction: Karla Knight, Spaceship Note (The Fantastic Universe), 2020

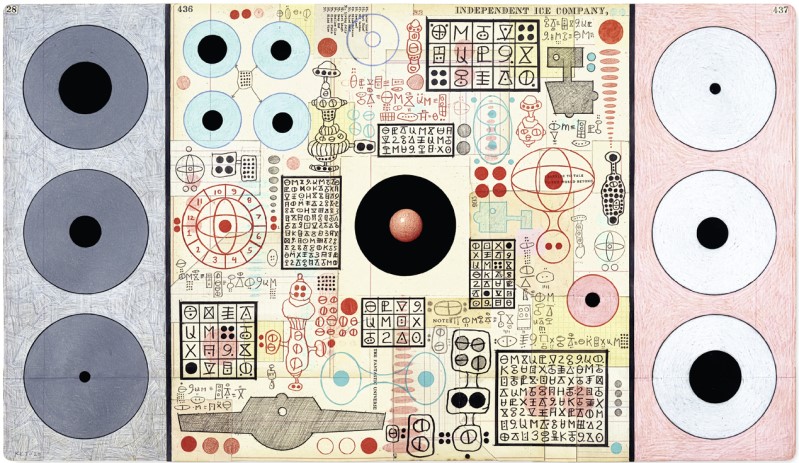

Ways of Seeing Abstraction:

Karla Knight, Spaceship Note (The Fantastic Universe), 2020

Most

people still understand abstraction as a concentration on form. It is

viewed as an art movement which is used to express aesthetic ideas,

orders, philosophical ideas or inner feelings, but which does not have

much to do with everyday reality. However, especially in times marked

by crises, relevance and urgency are also expected from art, and it is

expected to make a statement on current social issues. Today, artistic

commitment is not conveyed exclusively through clear visual messages

and content, but increasingly through abstraction. For younger

generations, in particular, non-representational art is the means of

choice for addressing politics, religion, and social issues. Showcasing

works from the Deutsche Bank Collection, the exhibition “Ways of Seeing

Abstraction” at the PalaisPopulaire undertakes a thoroughly subjective

survey of international abstraction from postwar modernism to the

recent present, documenting the diversity and discursivity that lie

behind the idea of non-objective, “pure” form. On the occasion of the

exhibition, our series will show you works by artists who use

abstraction idiosyncratically and define it in new ways.

Karla Knight, Spaceship Note (The Fantastic Universe), 2020

© Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York

Even when she was a child, the supernatural was omnipresent for Karla Knight. Her father wrote books on "extrasensory perception," investigating topics such as the occult and UFOs. But there is another family influence that has had an impact on the American artist's enigmatic images: she observed that her little son invented his own letters and words during his first attempts at writing. And so Karla Knight began to create a distinctive artistic cosmos, which in its consistency approaches "Outsider Art." She combines references to abstract modernism, Dadaists like Max Ernst, and the visionary designs of architect Buckminster Fuller with science fiction, pseudo-scientific diagrams, and imaginary scripts suggesting hieroglyphs from ancient Egypt.

Her preferred working material is wastepaper, which Knight uses to organize her visual vocabulary: hieroglyphics, symbols, and reduced forms are arranged into compositions whose logic ultimately remains inscrutable. They evoke floor plans, game boards, or computer circuit-boards, appearing both familiar and alien. "It’s not about deciphering the work or the language," says Knight about her paintings. "It’s about living with the unknown." And this is perhaps the best way to grasp her work intuitively—as a portal into an archaic-futuristic parallel universe.